.jpg)

Semester-Long Success from Day One

As a college student, I became fascinated with the prospect of maintaining my academic grades while also taking (almost) every evening and weekend off from school. Since then, I have explored the systems, tools, and neurology that set apart the students who always seem to have an abundance of time and little stress and those whose grind sessions seem to produce more anxiety than papers. The culmination of that process is this: a four-point system for improving your academic experience from day one of the semester.

Crave Routines

We as people operate best when we have routines; we thrive on regularity. While the cliché “variety is the spice of life” is true (monotony is boring), any good cook knows that spices shine best against a basic background. Use some “time management hygiene” and learn to love the regularity of it; that way, you can enjoy the distractions and community opportunities without the stress or needing to rush your work later.

Use a Long-term Calendar for an overview of major dates.

The goal is to get all your due dates and major events plotted out in a format that lets you see the big picture easily. This helps prevent any assignments or big events from getting missed or growing too close without you noticing. We work best under fixed constraints, so help yourself out by adding your own “start-by” dates and breaking down big assignments with your own “artificial due dates” for key aspects. For example, add dates to finish your thesis, research, outline, and first draft for a major paper.

Create a Weekly Schedule

Often, when students “don’t have enough time,” the real issue is a failure to allocate the time they have. The solution is to know how you will spend your time each day. Use the ARC weekly calendar to plot out your “average” week. Include all your fixed commitments, like class times, chapel, church, and small groups. Then, add flexible events you need to do, like eating meals or exercising. Next, set aside time for studying; I recommend you create “blocks” of time for big assignments, small assignments, and reading. Some students like to further break this down per class, but these three are often sufficient to get you started. Dedicating these work times greatly reduces the likelihood of procrastination and “not having enough time.”

To-Do List

The last piece of this system is a to-do list. I recommend setting aside time at the start of each week to create a master list for the coming week and then creating a list each day from that. Your Long-Term Calendar will help you decide what you need to accomplish. When you sit down to study, pull out your To-Do list, and pick an item or two to make the session's primary goal(s).

This system isn’t meant to restrict your time. You can adjust it as it suits your needs and move things around to account for an unusual day. You will find that planning your time increases your free time and flexibility.

Reduce Friction

A primary benefit of the system above is that it reduces the “friction” of making time for assignments and deciding how to use that time. Friction is anything that causes resistance or increases the difficulty of focusing on your work and getting things done. Many things, such as hunger, a messy room, or a noisy workspace, can create friction.

Here are three primary types of friction:

Study Session Goals

Many students go into a study session without a clear project to work on or an outcome to aim for, and so they spend most of their time moving from task to task and getting “set up.” Avoid this by taking 30 seconds at the start of each study session to consult your to-do list and determine what you will work on for this session.

Stimuli

Sensory input may be the biggest focus killer. Take time to consider your study environment and what makes it distracting (or what about it helps you focus) and seek to alter those elements either within that space or by finding somewhere else to work. Some stimuli to consider are temperature, noise, how many people are around, and your chair.

Other Tasks

You’ve dedicated yourself to writing your history paper, adjusted your workspace, and just as you start writing, you remember you need to call your mom this week, and all your focus vanishes. Keep a notepad or app handy while you study, and whenever a task, insight, or distracting idea comes into your mind, export it from your mind onto the page. This eases our minds because we know we won’t forget that important thing later but can quickly get back to the task at hand. This is a surprisingly simple method that saves many students from losing focus.

Leverage Habits

Remember the first time you drove a car, how you actively had to think about every detail and felt tired quickly? Now, shifting, checking your speed, moving your feet between the pedals, and many other aspects have become “habits,” and you can drive for longer.

A habit is simply a cue or trigger that activates a routine in us to receive a reward of some kind. As a student, you have dozens or hundreds of habits you probably aren’t aware of. By thinking about your habits intentionally, you can learn what cues are creating certain routines and what reward you are driven by, and therefore change that routine or build new ones.

Consider your habits in the following areas and how you can change them to work better for you.

- Dedicate one or two spaces to always study so you begin associating that space with your study mindset. Keep this space separate from where you rest or socialize for better results.

- Pick one or two playlists (choose a genre you like, just make sure there are no lyrics) for certain activities to get in a “study mindset.” Find one each for reading, writing, and one other subject area.

- Wake up, eat, and go to sleep at roughly the same time every day (even on weekends) to feel more nourished and rested.

Build Systems

Most “study tips,” be they from books, professors, or online, are offered as isolated ideas. This encourages students to see “studying” as one thing, usually reading over their notes before an exam. A study system encourages students to see studying as the entire learning process.

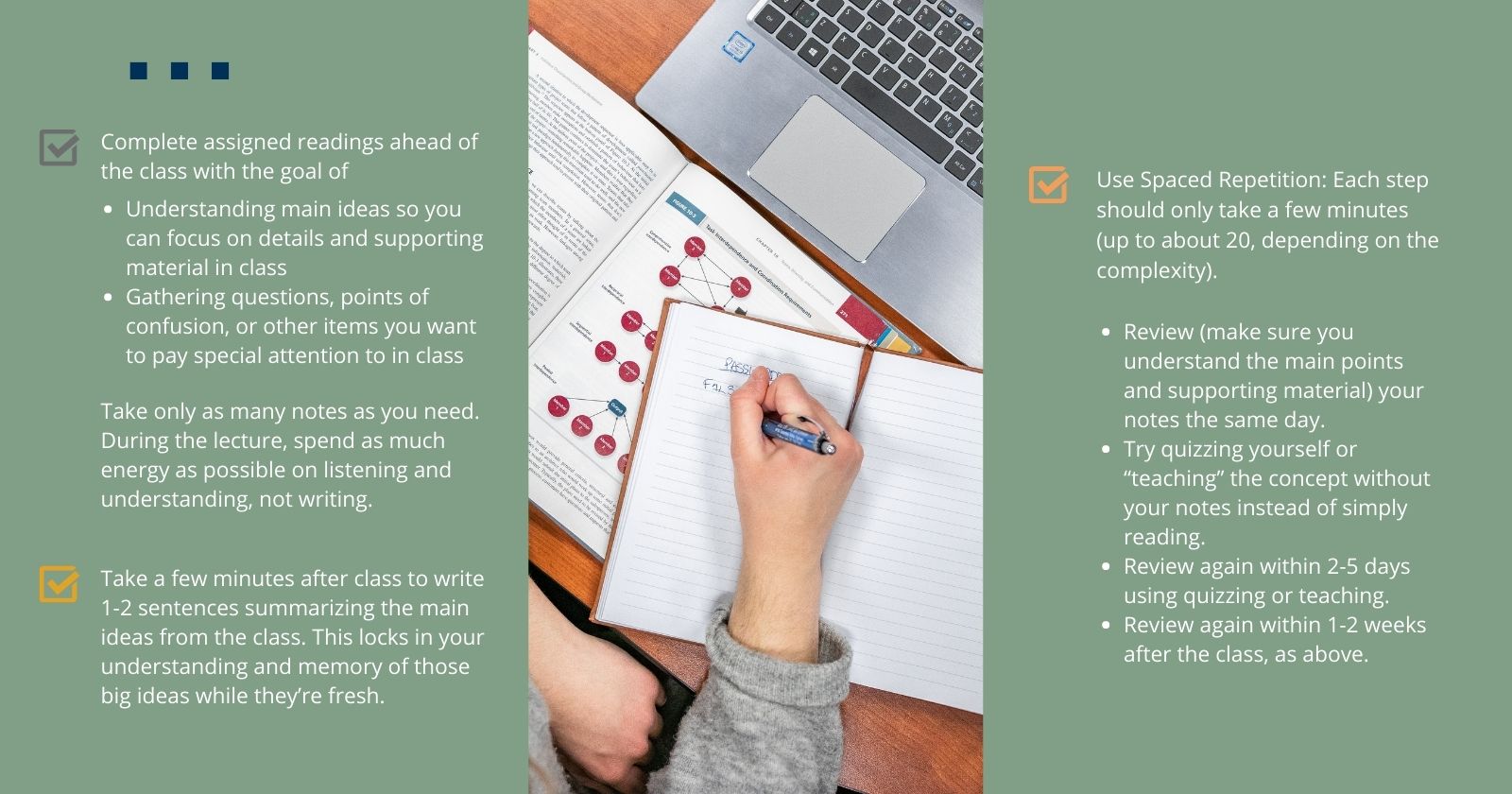

Try adapting the following system for yourself:

Using this or a similar systematic approach helps pace out the work of recollection and memory and takes advantage of the ways our brain works best.

To learn more about improving your academic experience, go to Briercrest's Academic Resource Centre webpage or check out these helpful articles: